We have a Scientific Literacy Problem

Scientists, Lock-in: Five ways people misunderstand science.

I write this as a mother thinking about my child’s future in this country, as a scientist concerned about the erosion of our scientific institutions and expertise, and as someone who refuses to feel hopeless. Hopelessness is convenient. It tells us there is nothing we can do. It excuses disengagement and forgoes accountability. I refuse to do that. So, lock-in. We have work to do.

Recently, I spoke to a class of incoming freshmen and emphasized the importance of recognizing expertise as a strength, not a weakness, the value of statistical literacy, and, most importantly, that “science is not finished until it is communicated” (Sir Mark Walport). Most scientists I know entered science not just to understand the world, but to improve it. Somewhere along the way, we forgot that science is for the public. When we fail to explain it, those gaps are filled by people who pretend to. More of us have to step up to explain what science is and how it generates knowledge.

Science is Wildly Misunderstood

From the years I have spent as a science communicator online, I have gathered that most public debates about health, science, technology, and risk today are not really about facts. They are about how people think knowledge works (which is also influenced by their cognitive biases, but that’s a separate post). Many people are taught science as a static list of dead facts, a textbook of things we already know. That framing is misleading, and it fuels misinformation. Science is a method for generating increasingly reliable knowledge under uncertainty. That distinction matters.

Largely, what I observe is that people don’t just misinterpret science, but try to reverse its epistemic nature entirely. Epistemic simply refers to how we know what we know, and much of today’s misinformation comes from not understanding how the process of generating that knowledge works, what that process is designed to do, and what it simply cannot do. But people are not just misinterpreting science; they are trying to replace its logic with belief, intuition, and identity.

So today I want to explain how science is misunderstood and, in a follow-up post, the loopholes pseudoscience uses to reject it.

1. Self-Correction Is a Feature, Not a Bug

First, let’s talk about the most common misunderstanding: that self-correction is a flaw. Most people experience science the way they do their iPhone: new, shiny, unbothered, and finished. They do not witness the endless iteration of sequential failures and troubleshooting that engineers and scientists must learn from to surmount key challenges in product design, performance, yield, and scalability.

I work as a senior scientist, and my role is literally finding out how and why things fail. That’s at the heart of innovation. But many people just don’t see that on a day-to-day basis. If your phone shipped with every corrective action ever taken to fix known failures, you wouldn’t have enough time in your lifetime to read the documentation. I’m not exaggerating. Science works that way. People see the end product: a guideline, a consensus statement, a textbook conclusion. What they don’t see is the constant testing, rejection, revision, and refinement. That refinement doesn’t really end (btw, that doesn’t mean science is unreliable either, but that’s separate; see below).

That is why when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, science got such a terrible rap for doing what it is supposed to do: change and self-correct with new information. And COVID forced the public to watch science happen live. The virus evolved, new variants emerged, and some escaped parts of the immune protection vaccines initially provided. And yes, we uncovered new risks about our vaccines. So scientists updated their models, updated their risk estimates, and their recommendations. But instead of recognizing this as science functioning correctly, many people concluded that “They lied,” or that “You can’t trust science.”

And the pandemic didn’t just make science visible in real time for many who hadn’t “seen” it directly; it made it visible under extreme uncertainty and crisis conditions. People weren’t watching calm, slow, academic refinement. This was science operating while people were dying, hospitals were overwhelmed, supply chains were breaking, and decisions had to be made before perfect data existed. That matters.

Usually, uncertainty is resolved quietly, but with COVID, uncertainty had to be managed in public, under pressure, with incomplete information, in a sea of misinformation, and with enormous consequences attached to every decision. Waiting for perfect certainty wasn’t an option (it seldom is in real decision-making). Doing nothing was itself a decision, and often the most dangerous one. So recommendations were made based on the best available evidence at the time, our real-world constraints, and the ethical need to reduce harm immediately.

That process was NOT deception, but actual evidence responding to reality. Science didn’t and doesn’t promise certainty. The issue I see is that people demand certainty from a system designed to reduce uncertainty over time. This leads me to my second point: convergence.

Disclaimer: There are bad actors, conflicts of interest, and institutional failures, and those certainly deserve scrutiny. But the idea that updating conclusions is evidence of failure is exactly backward. Self-correction is not a bug in science. It is the feature.

2. How We Generate Consensus: Strength AND Convergence

Someone asked me recently how we determine when science is “settled,” and how I decide which findings to “accept or reject”. I don’t love that word, settled, because it implies permanence, as if conclusions can never change with new evidence. In reality, scientific confidence is provisional. It grows stronger with better data, broader replication, and deeper understanding. Now, back to that question. The answer lies in the strength of the data, alongside convergence.

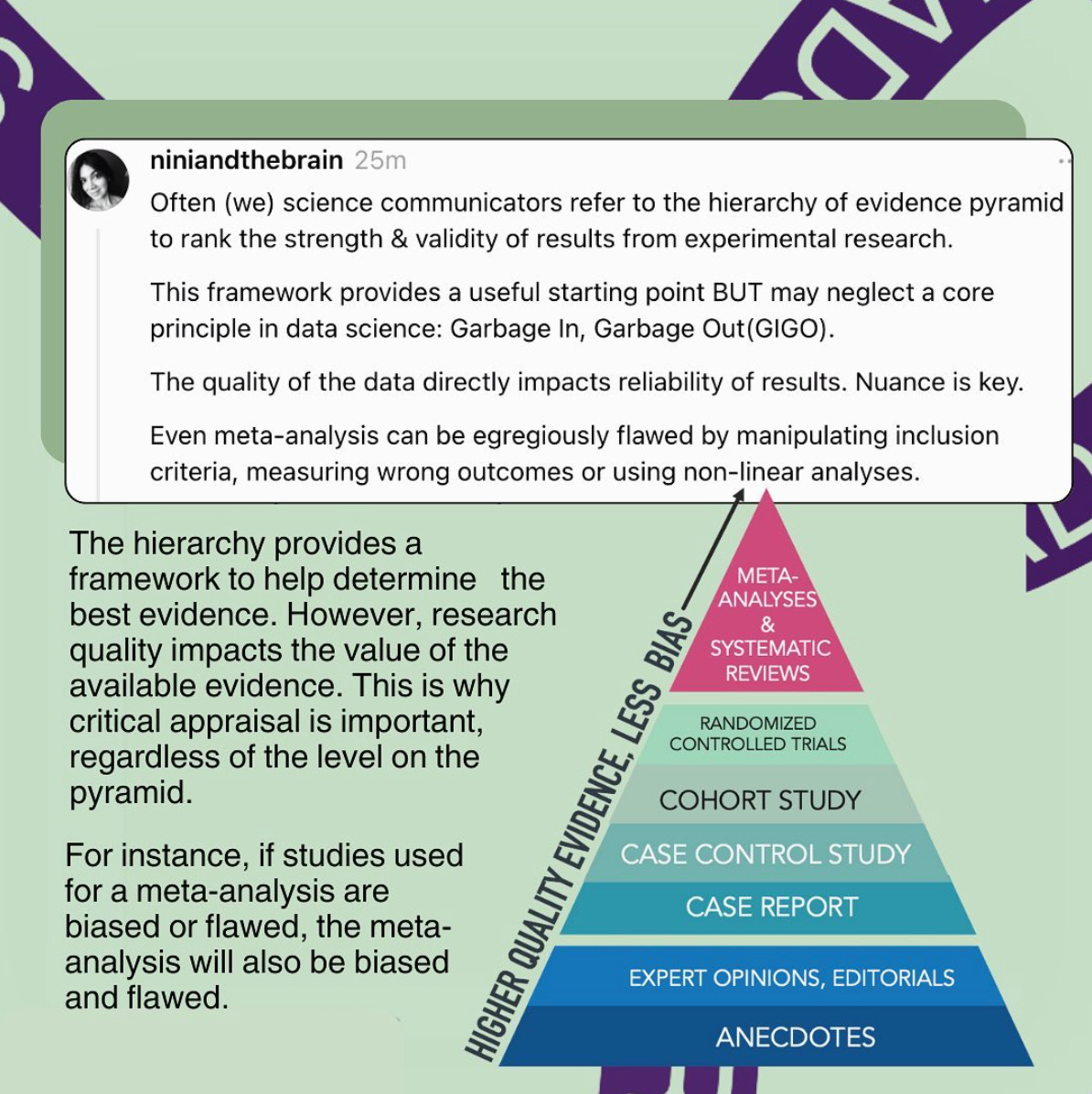

More than whether a study exists, one needs to first look at the strength and structure of the evidence behind it. I have referred to the hierarchy of evidence pyramid to rank the strength and validity of results. While this framework provides a useful starting point, it is key to note that the quality of the data impacts the reliability and validity of the results.

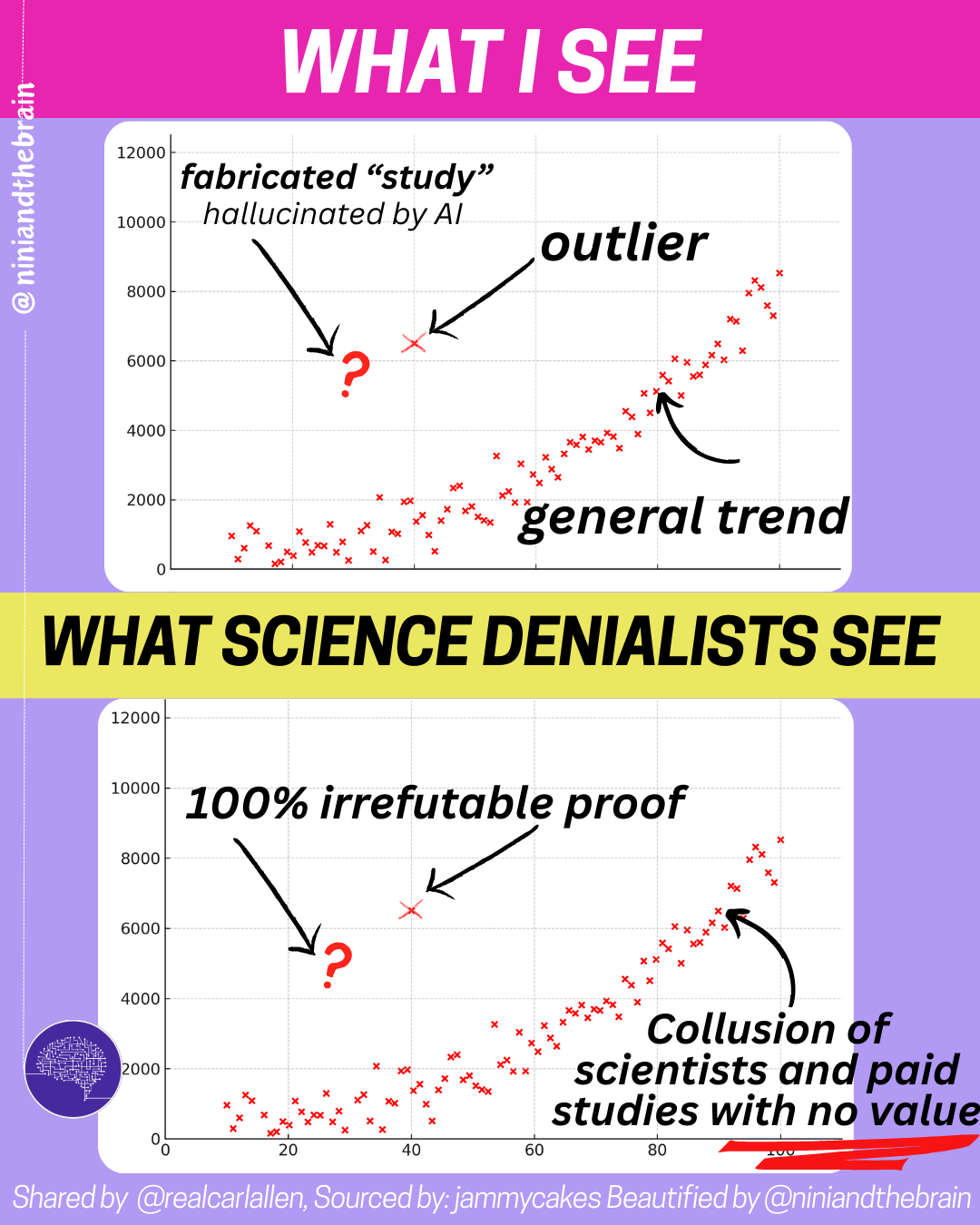

So while people will often cite studies, meta-analyses, even, to substantiate weak claims, that response reflects a misunderstanding of how evidence works. A robust conclusion warrants well-conducted studies. But beyond that, strong conclusions come from multiple high-quality studies, using different methodologies, showing consistent results, and involving large, diverse samples. Outliers exist in every field. They do not overturn the larger body of evidence on their own.

So, it is not just how a study is conducted, but whether its findings can be independently reproduced. That’s the whole point. Science does not advance through isolated papers. It advances through converging lines of evidence.

A typical process looks like this: observation and hypothesis, controlled data collection, revision of conclusions, replication, independent verification, and integration into broader models. Evidence accumulates across methods, populations, laboratories, and contexts. Reliability comes from convergence, not from any single result.

This is why treating individual studies as decisive is one of the most common mistakes people make. It is false balance. No serious scientific conclusion rests on one paper alone, even more so when single studies can be underpowered, biased, confounded, misinterpreted, or simply statistical flukes. Even well-designed or well-intended studies can produce misleading results (that is true for meta-analyses as well). Replication helps filter noise from the signal and shows whether findings hold up in the real world.

But there is another layer people rarely consider: publication bias.

Journals are more likely to publish studies that find small “effects” than studies that find nothing at all. Null results often sit unpublished. Over time, this skews the literature. So you can end up with dozens of small, weak studies showing tiny, inconsistent associations, while equally valid studies showing no effect remain invisible. This is exactly what we’ve seen in areas like 5G research or fluoride claims of neurotoxicity. Many low-quality or borderline studies report minimal effects (and are subject to many statistical flaws), while higher-quality studies showing no meaningful impact receive less attention. When only “positive” findings are visible, it can look like a real pattern is emerging, even when it isn’t.

This creates the illusion of evidence where little exists. Weak studies, amplified by selective publication and media attention, can converge around false conclusions. It is a statistical distortion.

Something is more likely to be true when the larger body of strong, well-designed, independently replicated evidence points in the same direction. Not when a handful of weak studies happen to agree. Convergence matters, but quality matters more (IMO). And without understanding that, it’s easy to mistake what could be statistical noise (as we see in so many fluoride studies) for knowledge.

That’s why serious evaluations rely on both the strength of the evidence and convergence (and not just either/or). The strength of the evidence depends on many other factors too (which I will tackle on its own). So we not only ask, “How many studies exist?” but also, “How good are they?”

3. Uncertainty Does Not Mean Unreliable or That “We Don’t Know”

All good science reports uncertainty. I’ve discussed this extensively because misunderstanding this point is one of the main reasons people conclude—incorrectly—that science is unreliable.

For instance, when we measure the effect of anything, we rarely get a single, perfectly precise number. Instead, we observe a range of values. In health data, for example, that range reflects differences across individuals, time points, and conditions. The best single summary of an effect based on the data, such as the average reduction in blood glucose, is called the point estimate. But a point estimate alone is incomplete. A confidence interval (CI) tells us how precise that estimate is. It answers a critical question: given the amount of data we’ve collected and the natural variability in those measurements, how far might the true value reasonably be from our estimate? Imagine trying to estimate the average height of everyone in a city. You can’t measure every person, so you measure a sample and calculate the average. But because you didn’t measure everyone, there is uncertainty about how close that average is to the true population value.

As Stanley Chan at Purdue put it: “From the data, you tell me what the central estimate X is. I then ask you, how good is X? Whenever you report an estimate X, you also need to report the confidence interval. Otherwise, your X is meaningless.”

More formally, confidence intervals reflect what would happen if you repeated the same study many times. If we say we are 95% confident, that means that across many repeated samples, about 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true value. It is a statement about reliability across repetitions, not about guesswork.

This is where people often get confused. They see ranges, intervals, unknowns, probabilities, and margins of error and assume these are signs of weakness. They interpret probabilistic language: “likely,” “increases risk by,” “reduces risk by,” “on average” as scientists being unsure or evasive.

In reality, probabilistic data is how complex systems are described honestly. Biology, medicine, climate, and human behavior are variable systems. No serious scientist expects identical outcomes in every individual. What matters is not perfect data, but rather reliable prediction over time. When medicine says a treatment reduces risk by 50%, people sometimes say, “So it might not work?” and miss the point entirely.

The goal is not certainty or 100% efficacy (because rarely anything is), but rather improved prediction. Only then can one focus on improving the outcomes. Furthermore, a treatment that reliably shifts outcomes in a favorable direction is valuable, even if it does not work for everyone. A model that predicts trends accurately is useful, even if it cannot forecast every individual case.

And over time, good science does something even more important: it shrinks that uncertainty. As more data accumulate, methods improve, and models are refined, confidence intervals narrow, predictions become more precise, and error margins contract.

Uncertainty is not a flaw. What would actually be unreliable is pretending certainty where none exists (guess who does that?) A claim with no error bars, no probability ranges, and no acknowledgment of limits is not more trustworthy. It is less.

Every high-stakes field depends on quantified uncertainty. Engineering, medicine, aviation, and infrastructure are built on tolerances, safety margins, and reliability estimates. We trust bridges, airplanes, and medical devices precisely because their risks have been measured and bounded, not ignored.

Like convergences, scientific reliability comes from predictability. When multiple studies, using different methods, repeatedly produce estimates whose confidence intervals overlap and tighten over time, we gain increasing confidence that we are converging on the truth, and our knowledge becomes more stable. Not by eliminating uncertainty, but by measuring it, managing it, and steadily working on shrinking it.

That is what trustworthy science looks like.

4. Plausibility is NOT the same as evidence or proof

Now, let’s extend this to another major misunderstanding: the belief that plausibility is the same as proof, because plausibility lives in the realm of uncertainty. Talk to any of the quantum consciousness peeps who continue to think that because it could happen, it is happening (that quantum effects drive consciousness), and you will see what I mean. Many claims sound convincing because they appeal to biological or physical mechanisms.

“This affects inflammation, so it must improve health.”

“This interacts with cells, so it must work.”

On the surface, these statements feel scientific. They use the language of mechanism. They sound grounded in biology or physics. But plausibility only tells us that something could work or be true. It does not tell us how likely it is to work, for whom, under what conditions, or with what risks. A mechanism suggests a possible pathway. It does not tell us whether that pathway is strong enough to matter in real, complex (human) systems. With regards to health data, biology is noisy, human populations are heterogeneous, and feedback loops, compensatory mechanisms, and unintended effects are everywhere.

That is why so many ideas that look promising in cells, in animals, or in theory fail in real people or experiments. History is full of plausible mechanisms that went nowhere. The supplement industry is riddled with a whole lot of plausibility and very little proof of efficacy. Just because a vitamin plays an important biological role—like vitamin D—does not mean taking more of it will reliably improve health outcomes. Plausibility generates hypotheses, but well-designed trials determine reality.

This also ties into what philosophers call the argument from ignorance: the idea that if something has not been completely ruled out, it must therefore be true, again, many citing plausibility. We see this repeatedly with vaccine-autism claims. Despite dozens of high-quality, large-scale studies converging on finding no link, some argue that because science cannot prove absolute impossibility (with the newest request being RCTs on ALL other vaccines), the claim remains “open” because it could be true.

But by that logic, we could claim that broccoli causes autism. Or satellites. Or transistors per CPU. Or Wi-Fi routers. Or any exposure you can name. The inability to rule out every hypothetical scenario does not make a claim credible. When fringe views are framed as just as credible—simply because they could be true—one blurs the line between evidence and speculation.

Science works by weighing probabilities and looking at how the evidence converges, not entertaining infinite possibilities because of supposed plausibility. Anything being plausible does not translate to everything being equally likely. We do not treat every unproven suspicion as equally proof. Just as I cannot prove with absolute certainty that my neighbor is not secretly a criminal, that does not justify calling the police. We require evidence strong enough to justify action.

That is how rational systems function.

When people elevate mere plausibility and unresolved uncertainty into “proof,” they are reversing the logic of science. They are treating what is merely possible as if it were probable. And that confusion—between what could happen and what reliably does happen—is at the heart of much modern misinformation.

Yes, science involves uncertainty. Especially in health science, where results can be probabilistic. But uncertainty doesn't mean we don't know. And a remote possibility, especially when rooted in outliers or sloppy studies, is not the same as reasonable doubt or evidence. Relying on the small chance of robust science being wrong to reject the much larger probability of it being right is not neutral or objective either.

5. People confuse access to information with expertise

Lastly, and this one really matters because it fuels all the others.

If someone believes: “I’ve seen the information, so I understand it,” then:

Self-correction looks like lying

Plausibility feels like proof

Uncertainty feels suspicious

Single studies feel decisive

Nowadays, information is ubiquitous, and people assume that reading papers, watching podcasts, or Googling studies makes them qualified to interpret complex data, without training in statistics, methods, or domain context.

Look, I get it. I love learning. I love digging into complex systems and trying to understand how things work. That instinct is healthy. Curiosity is a strength. But curiosity without humility risks becoming arrogance, or as we call it, Dunning-Kruger personified.

But I can tell you, as someone with niche technical expertise, I genuinely feel like I “don’t know anything” a lot of the time. Not because I’m uninformed, but because the deeper you go, the more aware you become of what you don’t know.

I still ask questions every day. I still rely on people who know more than I do. I still defer to specialists. That’s not a weakness. That’s how serious professionals operate. The problem is that access to information has created the illusion of competence.

Just because you can download a paper does not mean you can evaluate its methods or outcomes, interpret its statistics, identify confounders, spot subtle biases, or tell whether the results are robust, fragile, or even relevant. None of that is intuitive. It takes years of training and experience. And that’s not an insult. It’s true for all of us. I say this often: I can read a flight manual. That does not mean I can fly a plane. I can read legal code. That does not mean I can practice or understand the intricacies of the law.

Real expertise is built through repeated exposure to failure, feedback, peer review, and correction. It comes from learning where mistakes hide. Ironically, the more you actually know, the less confident you are in simple answers. People who truly understand complex systems rarely speak in absolutes. They talk in ranges, probabilities, limitations, and tradeoffs. They know how fragile conclusions can be. The people most convinced they’ve “figured it out” are often the ones who’ve never had their reasoning stress-tested ( I am stress-tested EVERY DAY). So this isn’t about telling people to “shut up and trust authority.” It’s about recognizing that expertise exists for a reason. Our world would be hugely inefficient if everyone attempted to be an expert in everything.

Where do we go from here?

We need more scientists to communicate and engage better and more consistently with the public, and on par with that, we need systems that make science more accessible. That means more scientists on social media, community outreach programs, fireside chats, and requiring science communication classes. When scientists disagree, we also need to help people understand why and whether the arguments are valid.

Science is not a collection of facts; it is a process and system designed to detect error, reduce bias, integrate evidence, update beliefs, and improve predictions. It must be viewed through the lens of continuous improvement, not a static set of givens. It works slowly and imperfectly, but yet better than any alternative humanity has ever created.

Most attacks on science come from misunderstanding its epistemology. Once you understand how knowledge is actually produced, the noise becomes easier to discern, and the signal becomes harder to ignore.

Pseudoscience exploits many of these misunderstandings. It treats uncertainty as failure, change as incompetence, access as expertise, outliers as the norm, and revision as proof of fraud, all in an attempt to adhere to a fixed set of beliefs. Outside of discussing science, we must also emphasize how to spot the tools of pseudoscience because people encounter these daily, distorting their reality. But real science identifies the best evidence and updates as the data changes. If you reverse that epistemic framework, if you demand unchanging conclusions in a changing world (and by that, I mean robust, replicable evidence, not your sister’s friend’s grandfather’s anecdote or some outlier or weak study taken out of context), you don’t get truth. You get dogma.

To be continued…

Until next time, stay grounded, keep learning, and keep asking good questions.

-Nini

I’m Nini. My expertise spans from sensor design to neural interfaces, with emphasis on nanofabrication, data science & statistics, process control, and risk analysis. I am also a wife and a mom to one little girl. TECHing it Apart emerged from my drive to share in-depth insights on topics I cover on Instagram (@niniandthebrain), where I dissect misinformation that skews public health policy and misleads consumers through poor methodology and data manipulation, as well as trends in health technology. Content here is free, but as an independent writer, I sure could use your support!

This captures the heart of the issue very well. The other question is "why do people not want to learn to become more scientifically literate?" Clearly there is an aversion to this. Is it that it is easier to pretend to know everything than trust in a process that builds on itself and refines towards solutions? Is it that it is far easier to criticize , and try to undermine scientific information in a social media world where it makes them seem more of an "expert"? Is it a failure of how science in taught is schools, where "answers" are presented as definitive?

Thank you for this. I hope I can keep some of these arguments in mind when I talk to folks who believe whatever they get from the media and spout it. I will put bullet points on my phone for future reference.